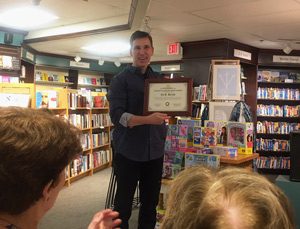

Ted W. Baxter, author of memoir Relentless, aphasia advocate, and former University of Michigan Aphasia Program (UMAP) client, returned to Ann Arbor to give voice to the millions of people in the U.S. with aphasia who may not be able to speak for themselves. As an Aphasia Awareness Advocate, Ted helped UMAP kick off Aphasia Awareness Month. He spoke about his journey back from stroke and subsequent aphasia and read from his book during a public event at Nicola’s Books in Ann Arbor on June 5.

June is the nationally recognized Aphasia Awareness month, with the goal of bringing about understanding, support, and access to resources for people with aphasia and their families and care partners. The theme this year is let’s Talk About Aphasia.

Aphasia is an acquired communication disorder. A person with aphasia may have trouble speaking, understanding, reading and/or writing, while their intellect remains intact. Stroke and head injury are the most common causes.

Find and share social content using the hashtag #TalkAboutAphasia.

Coming Back from Stroke and Aphasia

Ted spoke about his experience with stroke and aphasia and read an excerpt from his memoir, Relentless, detailing the aftermath of the massive stroke that left him fighting for his life and subsequently his words. Writing the book and sharing his story is his way of raising awareness about aphasia, something that affects at least 2 million people just in the U.S. with nearly 200K new cases a year.

Relentless is, in Ted’s words, about “recovery, being frustrated, being alone, battling back, having a great support system, and having courage.”

Ted’s Aphasia Journey

Ted was 41, at the top of his game, and excelling at his dream job — when everything changed.

“In a split second,” he said, “I lost the power of language. I felt petrified, helpless, alone.”

He had a massive stroke that changed everything. Ted could no longer walk or talk. He went to an inpatient program for eight weeks and then attended various outpatient programs. His third outpatient program was the U-M Aphasia Program.

“I’ll tell you right now, bar none, UMAP is the premier aphasia program I attended,” he said. “UMAP gave me the foundation to get my speech back.”

Ted shared information about his aphasia to help put it in perspective for someone who has never had aphasia. In the year after his stroke, he had a working vocabulary of about 1,000 words, “mostly nouns and basic verbs.” A four-year-old usually knows about 4,000 words and an adult usually has a vocabulary of 20,000 to 35,000 words. Ted said he just had to practice — a lot. He kept relearning words and phrases. Repetition was key.

He used flash cards meant for children to relearn words for things and to practice saying them. He started with basic words for everyday items and eventually graduated to more challenging topics. He recalled reading the front of a card about a Portuguese explorer and pushing his mouth to say what his brain knew: Magellan.

“I’m still practicing,” he said. “It’s the only way I can get better.”

Community and Acceptance are Key

Ted also spoke about how much the aphasia community means to him. It’s nice to talk to other people who have aphasia too, he said, because they understand and you know you’re not alone. Often, listeners without aphasia will try to fill in the blanks of what Ted is trying to say — a common experience for those who have aphasia.

Ted also spoke about how much the aphasia community means to him. It’s nice to talk to other people who have aphasia too, he said, because they understand and you know you’re not alone. Often, listeners without aphasia will try to fill in the blanks of what Ted is trying to say — a common experience for those who have aphasia.

“Don’t do that,” he said. It’s frustrating for someone who is trying to participate in the social world and trying to communicate. They just need a little extra time to say what they want to say, so patience is key.

“Regular people, they don’t really get it,” Ted said.

Finding a support system, however, is an important part of recovery. Ted mentioned something else that helped him with his recovery: acceptance.

During the question-and-answer session following the book reading and talk, an audience member asked Ted about getting back into being social. He said for a time following the stroke, he kept putting off seeing friends and family because he wanted to be “better,” he didn’t want them to see him as he was.

He was trying to get to a point where he could show them — and himself — that he was “back.” But that thought might have been holding him back.

“I’m not going to be the person I used to be,” he said. “To get that in my mind took a long time, but at the point I accepted that, my recovery became a lot more, a lot speedier.”

Director of the University Center for Language and Literacy, home of UMAP, Dr. Carol Persad said the tenacity Ted and others with aphasia demonstrate is a testament to their strength and the human spirit.

“I am still in awe of Ted’s determination and recovery in the face of his massive stroke,” Dr. Persad said. “His hard work and relentless approach are a great example to so many people with aphasia. Often times people with aphasia and their loved ones are told that there is no hope or that this is all the progress you can expect once you hit 6 months to a year post injury. And while it’s important to keep expectations realistic, there is always room for hope. Ted demonstrates that well as he continues to fight and get better 14 years after his stroke.”

Advocating for Aphasia

At the event, Dr. Persad presented Ted with an aphasia advocate award, thanking him for the work he’s done on behalf of the aphasia community. UMAP will continue to focus on increasing aphasia awareness throughout the month of June, and beyond.

At the event, Dr. Persad presented Ted with an aphasia advocate award, thanking him for the work he’s done on behalf of the aphasia community. UMAP will continue to focus on increasing aphasia awareness throughout the month of June, and beyond.

If you’d like to become an UMAP aphasia advocate, helping people to understand what aphasia is and what they can do to help build a supportive community, please go to this link to fill out an application and we will contact you with future opportunities. Both people with and without aphasia are invited and welcome to participate in the advocate program.